For centuries, russia has tried to rewrite ukrainian history, in particular by plundering ukraine’s cultural heritage. With the help of stolen artifacts, the terrorist country has for centuries fueled imperial myths about the diversity of russian culture, the continuity of its artistic tradition, the “brotherhood” of Ukraine and russia, and the absence of differences between our peoples.

📰

From history. One of the first known cases of theft of Ukrainian cultural monuments by russia was the theft of the Vyshgorod Icon of the Mother of God, which the Patriarch of Constantinople presented to the Kyiv prince Mstyslav the Great. It was kept in Vyshgorod and was considered the greatest shrine of Kyiv Rus. In 1155, Andrei Bogolyubsky, son of the appanage prince of Rostov-Suzdal, founder of Moscow Yuri Dolgoruky, stole the shrine during an attack on Kyiv and took it to the Assumption Cathedral of the then Volodymyr-on-Klyazma (now the city ofVladimir in the russian rederation). The icon was “rebaptized” — it is called Vladimir — and it is said that it “has saved russia from misfortune and adversity many times.”

And now, since 2014, russia has been actively pursuing a policy of aggression not only against the lands of Ukraine, but also against its cultural heritage. UNESCO estimated the damage to Ukrainian cultural heritage caused by russian aggression as of February 24, 2023, at $2.6 billion. The New York Times calls the looting of Ukrainian museums the largest since World War II.

The shrines of St. Mykhailo's Golden-Domed Cathedral. It is known that sacred art in Ukraine suffered the most from theft during the Soviet era. This fate befell, in particular, St. Mykhailo's Golden-Domed Cathedral, the main cathedral of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. It was built in 1108-1113, and on August 14, 1937, this unique monument of national and world culture was blown up by order of the Communist Party of Bolsheviks. Before demolition, the mosaics and frescoes created during the construction of the temple were removed from the walls of the cathedral. “These mosaics and frescoes were created when Moscow did not yet exist, so it was necessary to transfer the entire history from Kyiv to Moscow. And they did so for centuries,” scientists emphasize.

In the photo: St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral, early 20th century.

In the photo: St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral, early 20th century.The further fate of the monuments preserved in the 1930s from St. Mykhailo's Golden-Domed Cathedral is sad and confusing. A few years after the demolition, some of them ended up in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. During World War II, the Nazis took most of those that remained in Kyiv to Germany, and then returned them to russia in the process of restitution under a bilateral agreement between the Soviet Union and Germany (Ukraine was bypassed). Many years later, only 11 frescoes were returned to Kyiv, some of which were damaged. The rest of the valuables — frescoes and one mosaic fragment (at least 18 museum storage units) — were distributed in russia between the Hermitage, the russian museum (in what was then Leningrad), and the Novgorod Museum. Today, the aggressor country continues to flaunt the Ukrainian heritage of the princely era, shamelessly passing it off as its own roots. In particular, the Tretyakov Gallery displays frescoes, mosaics, and slate reliefs from St. Mykhailo’s Monastery in its permanent exhibition “Old russian Art. The Pre-Mongol Period.”

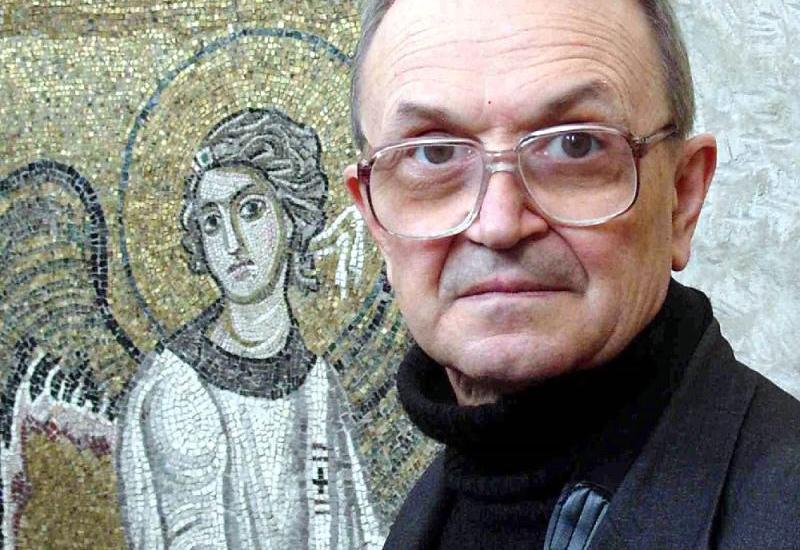

Our days. Yurii Oleksandrovych Korenyuk, a participant in those events, candidate of art history, associate professor of the Department of Graphics at the National University of Arts, tells about the return of the historical treasures of St Mykhailo's Golden-Domed Cathedral from russian museums to Ukraine. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, he was a member of the intergovernmental Ukrainian-russian commission on the return to Ukraine of artistic heritage that had ended up in russian museums.

As the art historian recalls, the largest mosaic composition from St. Golden-Domed Monastery, “The Eucharist,” was immediately installed in St. Sophia Cathedral (now the National Reserve “St. Sophia Cathedral”), The best-preserved mosaics and frescoes were transferred in 1936 to the newly created Kyiv State Museum of Ukrainian Art (now the National Art Museum of Ukraine). The museum exhibition with artifacts from St. Mykhailo’s Cathedral opened in April 1937, but at the end of that year, the museum was closed and its first director, Pymon Rudyakov, was shot. In July of the following year, 1938, an expedition led by an employee of the Tretyakov Gallery arrived from Moscow. From the collections of the closed Museum of Ukrainian Art, they selected the mosaic “Demetrius of Thessaloniki,” a mosaic ornament, a fresco of St. Mykhailo's , and a slate bas-relief for an exhibition in Moscow dedicated to the 750th anniversary of “The Tale of Igor's Campaign.” The transfer document included a note: return shipping (return delivery) at the expense of the receiving party (the Tretyakov Gallery). They are still returning it...

“Demetrius of Thessaloniki” says Y. Korenyuk, "is the most famous mosaic from the early 12th century, taken from St. Mimykhailo's Cathedral. It is a work of the highest level of craftsmanship by Byzantine and Old russian masters. The saint is depicted as a warrior, with a shield, spear, and sword. Now, in the rebuilt St. Mykhailo’s Cathedral, you can see a modern copy of the mosaic depicting Demetrius of Thessaloniki in the same place where it was in the 12th century (the southern edge of the pillar in the altar area)."

In the photo: The remains of the walls of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral after the explosion on August 14, 1937.

In the photo: The remains of the walls of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral after the explosion on August 14, 1937.But let's return to history. In 1939, St. Sophia Cathedral became an independent museum, and its employees planned to organize an architectural exhibition there. They reminded their russian colleagues about the return of the seized exhibits. Those documents have not been preserved in Ukraine, but one letter was found in the Tretyakov Gallery archives. “In the late 1990s,” Yuriy Oleksandrovych continues, "the russians ‘forgot’ to make a copy of it at the request of the Ukrainian commission, so our scientists had to secretly rewrite the text. The official response regarding the return of the exhibits stated: if the Tretyakov Gallery exhibition loses these artifacts, it will distort the correct understanding of the development of ancient russian art and its sources." In the 1970s, their attempt to discuss the return was harshly cut short by the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine.

In the photo: Exhibition at the National Art Museum of Ukraine with St. Michael's mosaics, frescoes and slate reliefs, 1937.

In the photo: Exhibition at the National Art Museum of Ukraine with St. Michael's mosaics, frescoes and slate reliefs, 1937.In the 1980s, Y. Korenyuk worked on his dissertation and maintained business contacts with russian scientists, in particular with the Hermitage. He managed to see the exhibits taken from Kyiv in the storerooms and obtain information that some of them were kept in the museum's collections in Novgorod. He went there and asked to see the artifacts, but was refused on trumped-up grounds (the curator was supposedly ill). However, he managed to see photographs of the inventory cards. There were five frescoes, and on the back of the photos were their (russian) inventory numbers... So when negotiations began in the late 1990s on the return of the St.Mykhailo relics, the Ukrainian side provided a list of known museum valuables that had been taken away, including those that were in Novgorod. “Do you know this too?” – was the reaction of the russians.

“The first meeting on the return of the exhibits,” continues Y. Korenyuk, "took place in 1999 at the Tretyakov Gallery. The meeting was attended by representatives of the Tretyakov Gallery, the russian Museum, the Hermitage, the Ministry of Culture of the russian federation, and others. On our side were the director of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, representatives of the commission on the return of artifacts, and the head of the commission, historian and public figure Serhiy Kot. Based on rational considerations, the Ukrainian delegation agreed to the russians' proposal to focus on the monuments that ended up in russia after World War II during the first stage of negotiations.

The next meetings took place in 2001 and 2002. At that time, they communicated with the director of the Hermitage, M. Piotrovsky, who agreed to return some items, but his deputy (now the chief designer of russian symbols) was very dissatisfied with this decision and categorically opposed it. In the end, after lengthy documentary justifications, 11 fragments of frescoes were returned from the Hermitage between 2001 and 2004. They were transferred to the Museum of the History of St. Mykhailo’s Golden-Domed Monastery. The russians wanted to hold a joint grand opening of the exhibition. Therefore, the museum did not unpack the returned exhibits for a long time, and after the final deterioration of relations between russia and Ukraine, the exhibition was opened in 2007 without the “international” participation of the neighbors. Currently, the frescoes returned from russia to Ukraine are on display at the Museum of the History of St. Mykhailo's Golden-Domed Monastery.

“However, a significant part of the mosaics and frescoes of St. Mykhailo’sCathedral, as well as one slate relief, are still illegally held in russian museums. But over time, they must be returned to Ukraine,” the scientist is convinced.

In the photo: Serhiy Kot in the collections of the Novgorod Museum next to fragments of the Mikhailovsky frescoes, 2002.

In the photo: Serhiy Kot in the collections of the Novgorod Museum next to fragments of the Mikhailovsky frescoes, 2002. In the photo: Stolen Ukrainian relics are displayed at the Tretyakov Gallery in moscow

In the photo: Stolen Ukrainian relics are displayed at the Tretyakov Gallery in moscow