The dormitory of Igor Sikorsky KPI stands on a recently renamed street – Oleksa Tykhyi Street. Who is Oleksa Tykhyi and why has his name returned to the capital of Ukraine?

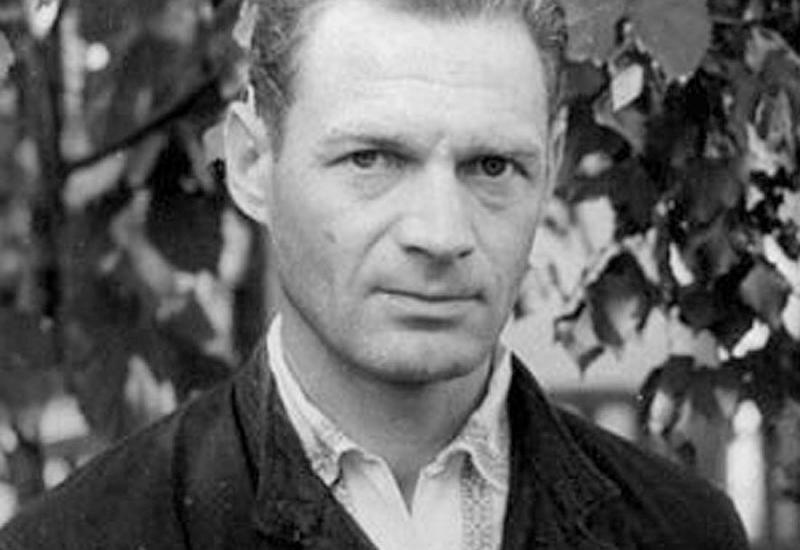

“He was supposed to be an outstanding teacher, but instead of a professorship, he got hard labor,” one of his colleagues says about him. His fellow countrymen call him “a true Donetsk Ukrainian.” Oleksa (Oleksiy) Tykhyi (1927–1984) was a human rights activist, political prisoner of the Soviet regime, educator, poet, linguist, and member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. One of the active participants in the dissident movement in Ukraine, he spoke out in defense of the Ukrainian language and culture in Donetsk Oblast and criticized the authorities' policy of russification of the region: “I want Donetsk region to produce not only football fans, rootless scientists, russian-speaking engineers, agronomists, doctors, and teachers, but also Ukrainian specialists who are patriots, Ukrainian poets and writers, Ukrainian composers and actors.”

Origins

Oleksii was born in the village of Yizhevka in Donetsk Oblast, where his family survived the Holodomor. He graduated from Oleksievo-Druzhkivska School in 1943. He studied at the Zaporizhzhia Agricultural Institute and the Dnipropetrovsk Institute of Transport Engineers. He graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow State University. He taught in schools in the Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk (then Stalino) regions. He consciously chose to work as a rural teacher in order to teach Ukrainian children “to do good to people, raise their material and cultural level, seek truth, fight for justice, human dignity, and civic responsibility.” “He was a teacher by vocation,” says Oleksa Tykhyi's son, Volodymyr. “He offered: give me one class, and from the first to the last, I, one teacher, will bring them to Moscow State University. Many students from the schools where he taught confidently entered the best universities in the country.”

Opposition

He was first arrested in 1948. He made a remark before the elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR: “What choice can there be when there is only one candidate?” He was 21 at the time. He was released after a “preventive conversation.” On February 15, 1957, he was arrested for the second time for writing a letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union protesting the Soviet occupation of Hungary. “The Magyars have the right to decide their own internal affairs,” wrote Oleksa Tykhyi, then head of the academic department at the Oleksievo-Druzhkivka secondary school near Kramatorsk. The regional court sentenced him to seven years in a strict regime camp and five years of deprivation of civil rights for “anti-Soviet agitation” and “slander against the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Soviet reality.”

After serving his sentence, Oleksa Tykhyi returned to his native village in 1964 to his mother, Maria Kindrativna—his father had died after the war. He started an apiary. Later, his son recalled: "My father brought a homemade violin from the camp, played a little, taught me, and strongly recommended that I learn foreign languages, in particular Polish, which he had learned in the camp. He advised me not to waste time, to listen to music and recordings while working with my hands. A year later, we bought bicycles and went to visit relatives in the Dnipropetrovsk region, covering 200 km in 1.5 days." Oleksii Ivanovych was banned from teaching humanities because he had served time on ideological charges, so he taught physics, astronomy, and English at night school. He subsequently changed a dozen professions: loader, burner, fitter, flaw detection operator, firefighter.

At this time, Oleksa Tykhyi began to actively engage in literary and human rights activities. His works were distributed in samizdat. “Will Donetsk be part of the Ukrainian nation in 10-20 years?” Oleksa Tykhyi asked in a letter to the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, Ivan Hrushetskyi, on April 24, 1973. “It seems that it will not be, if the main element of spiritual culture—language—is so intensively suppressed in all spheres of life, especially in educational institutions.”

With his excellent command of Ukrainian, Oleksa Tykhy compiled a collection of quotes from prominent figures around the world about their native languages, entitled "The Language of the People. The People,“ as well as a dictionary of linguistic distortions in the Donetsk region, ”Dictionary of Words Not Conforming to the Norms of the Ukrainian Literary Language,“ addressed to ”teachers, schoolchildren, as well as those who have neglected their native language or lost contact with it, everyone who wants to speak correctly and beautifully." He also wrote articles “Thoughts about my native Donetsk region,” “Reflections on the fate of the Ukrainian language and culture in the Donetsk region,” and “Free time of workers.” He also authored a number of journalistic works on pedagogy. He himself was an exemplary speaker of the Ukrainian literary language. He spoke correctly, greeting his interlocutors with a gentle smile. At the same time, he was a man of iron will, rare tolerance, kindness, and exceptional forbearance.

Hardships

In November 1976, Oleksa Tykhyi became one of the co-founders of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which was supposed to promote democracy and human rights. He prepared materials in defense of the Ukrainian language, distributed samizdat, and promoted the creation of a fund to help the families of political prisoners. His son recalls: "After the creation of the UHG, my father was detained several times — allegedly for robbing a kiosk — and summoned for questioning by the Kostyantynivsky District Executive Committee. At one point, he was advised to leave the country, but he refused: 'I am needed here, I can raise my voice in defense of those who are now in prison. A few months later, he was arrested again.

The trial of Oleksa Tykhyi and Kyiv human rights activist Mykola Rudenko, which resembled a farce, took place in the summer of 1977 in Druzhkivka. Tykhyi was sentenced to 10 years in a maximum security prison camp and five years of exile. “I am not guilty of anything for which I was given 15 years, but the law meant nothing to the judges and, apparently, will continue to mean nothing,” Oleksa Tykhyi wrote in a letter to his younger sister Shura from the camp in Mordovia. "I am in good spirits. I did only what is not only my right but also my duty; I did not commit any crime, and let those who imprisoned me suffer. Truth always prevails. True, sometimes after death."

Oleksa Tykhyi went on hunger strike many times to protest against the inhumane conditions of detention of political prisoners – violations of their rights to correspondence and visits. One such hunger strike lasted 52 days. In 1978, on the 17th day of another hunger strike, he suffered an intra-gastric hemorrhage. When the prisoner was brought to the hospital, his blood pressure was 70/40. The camp commander suggested that he write a letter of repentance. He categorically refused. “You will live in agony and not for long,” the KGB surgeon promised him (according to the memoirs of his cellmate Vasyl Ovsienko). During the last years of his imprisonment, Oleksa Tykhyi was constantly ill, his stomach could not tolerate anything, he developed intestinal adhesions, then metastases appeared, and he underwent several operations. Help was not provided in time: the X-ray machine broke down, there was no suitable doctor, etc. “I do not regret what I did, I do not hold a grudge against anyone. I did what I had to do,” he told his relatives during his last visit. On May 5 or 6, 1984, he died in a prison hospital in Perm. He was 57. His son Volodymyr was not allowed to take his father's body: “If you insist, the results of the bacteriological analysis may show hepatitis, and then you will never be able to take him away.”

We remember

According to Soviet law, the remains of a deceased prisoner were not returned to the family for burial in their homeland until the term of imprisonment had expired. Thus, even after death, Ukrainian dissidents remained prisoners of the Soviet regime. Only after five years, with great difficulty and numerous obstacles, were the remains of Oleksa Tykhy taken and, together with the ashes of Vasyl Stus and Yuriy Lytvyn, transported to Kyiv, where they were buried at the Baikove Cemetery on November 19, 1989. According to the recollections of those who participated in those events, more than 25,000 people took to the streets of Kyiv to bid farewell to their heroes under blue and yellow flags.

By decree of the President of Ukraine on November 8, 2006, Oleksa Tykhy was posthumously awarded the Order of Courage, First Class, for his civic courage and dedication to the struggle for the ideals of freedom and democracy, and on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the creation of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

Since 2008, the Oleksa Tykhy Society has been actively operating in Donetsk Oblast, publishing and promoting his works, organizing “Oleksa Readings,” competitions among young people for the best knowledge of the hero's biography and works, and bicycle races in his honor. Activists have achieved the opening of a 50 km long Oleksa Tykhy Avenue, connecting five cities: Kostiantynivka, Druzhkivka, Kramatorsk, Sloviansk, and Oleksievo-Druzhkivka.

Incidentally, in Oleksiyevo-Druzhkivka, on the grounds of the school where O. Tykhy studied and later worked, a monument to their fellow countryman was erected during the period of independence. At one time, russian occupiers vandalized it. After the town was liberated, the monument was restored at the expense of the community. It bears the inscription: “I was taught and I taught that man does not live by bread alone.”

Schoolchildren and students who participate in “Oleksa's Readings” write essays on a given topic, and the winners travel to Kyiv, where they met with L. Lukyanenko, V. Ovsienko, and his son, Volodymyr Tykhyi. Once, the topic was “Oleksa Tykhyi and the War,” and one of the participants wrote: “If Oleksa Tykhyi were alive, the path to victory, the path to peace, would be much shorter.”