The editorial board planned to publish this article last year, as 2023 marked the 240th anniversary of the first balloon flight by the Mongolfier brothers. However, for a number of objective reasons, we were unable to publish this article, so we are doing so now. It should be noted that the history of ballooning is extremely interesting, especially for polytechnics. And, moreover, it is a long one, because it was with that flight that its countdown began. Therefore, the author tells not only about it, but also about further steps into the blue space of aeronautics enthusiasts. Kyiv Polytechnic Fedir Anders was not lost among them...

The beginning of the air era

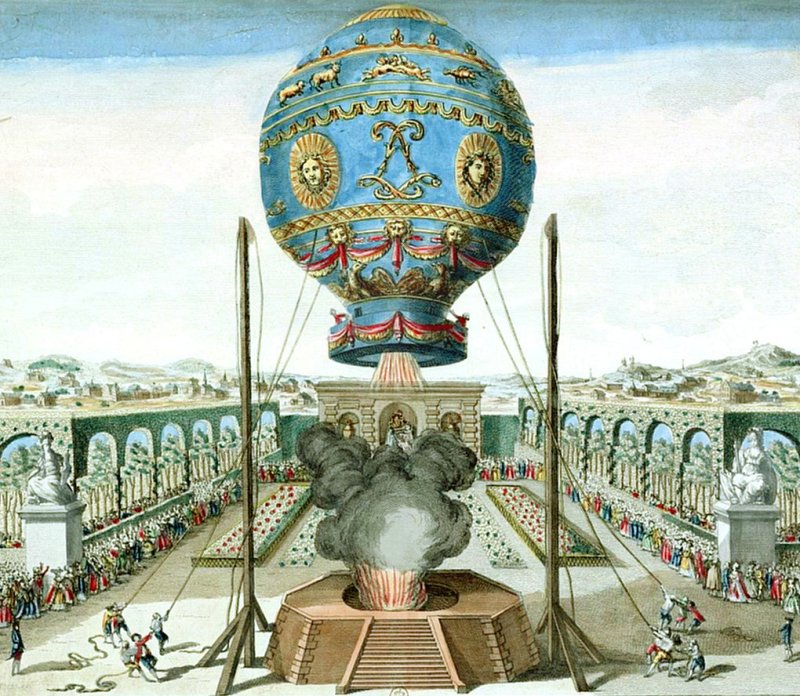

The real countdown of the history of the air age should begin on June 5, 1783, when Jacques-Etienne and Joseph-Michel Mongolfier lifted a 600 m3 balloon made of canvas into the air in the French town of Annonay. Filled with hot air, the balloon soared to a height of 500 meters and stayed in the sky for 10 minutes, covering 2 km.

The next step was a significant event in Versailles, which took place on September 19, 1783, in the presence of the royal couple Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The balloon then took off with the first passengers in the basket - a ram, a rooster and a duck. And on November 21, people took to the air for the first time on the balloon, which was named after its creators, the Mongolier: Jean François Pilatre de Rosier and the Marquis d'Arlande. Starting in the Bois de Boulogne (on the outskirts of Paris), the balloon rose about 1 km. After flying over the Seine and covering about 9 km, the balloonists landed behind the city rampart in 25 minutes.

At the same time as the Mongolfier brothers, another aeronautics pioneer, Parisian professor Jacques Charles, was working on his own project. On August 27, 1783, Charles successfully launched his balloon, made of silk soaked in a solution of rubber in turpentine. He obtained hydrogen for the balloon by exposing iron filings to sulfuric acid. After staying in the air for 45 minutes, the balloon scared the locals and landed 28 km from the launch site. The device was named after the inventor. Later, the professor improved the design of his balloon. He used a rope net to cover the balloon and transfer weight loads to it; a valve to release excess gas at high altitude; and an air anchor. Jacques Charles was the first to use sand as a ballast and to design instruments for measuring altitude. In general, the design was more advanced than the Mongolian.

The people were delighted with the success of the aeronauts and warmly welcomed them as national heroes. And rightly so! After all, from now on and forever, man is the master of the air!

The vague objections of the few opponents of the new vehicle were drowned out by the chorus of newly discovered aeronautical enthusiasts. The sobering of dreams came later, when, despite the outstanding success of aeronautics, it had to be admitted that balloons do not obey the aeronaut very well. Control is possible, but only "up and down". Otherwise, the balloon obeys the wind more than the aeronaut. Unfortunately, the authors of numerous projects have forgotten that the balloon acquires the same speed as the air flow that envelops it.

So, it was necessary to make the balloon controllable. This problem was solved by the French general and mathematician Jean-Baptiste Menier. It was he who proposed the project of the airship (from dirigere, which means "to control" in Latin). It was to be powered by the muscle power of 80 people who would rotate three propellers. This idea was used by another inventor, Henri Giffard, who, however, replaced people in his project with a steam engine.

Airships by Henri Giffard

On August 20, 1851, Giffard applied for a patent for the use of a steam engine for aeronautics (patent No. 12226). Since then, the idea of creating a controlled balloon has not left him. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the steam engine was already a fairly advanced engine, so Giffard decided to install it on his airship. However, an ordinary steam engine was not suitable for this purpose. He had to design and build a special, very lightweight machine. After a year of hard work, he managed to create a steam engine weighing 45 kg with a power of 2.2 kW. It was a record-breaking achievement for the time. The machine received steam from a lightweight boiler.

The shell of Giffard's airship was shaped like a sharp cigar, 44 meters long, 12 meters in diameter, and 2500 m3 in volume. The weight of the engine did not exceed 50 kg, and together with the boiler - 150 kg.

The shell was covered with a net. A wooden beam was attached to it from below, and a small platform on which the boiler, steam engine, and coal stock were placed. In front of the boiler, a place for the balloonist was arranged, limited by light handrails. The airship was powered by a propeller - a three-blade propeller with a diameter of almost 3.5 meters. To give the vehicle stability and controllability, the design included a special rudder-sail at the stern of the shell. Giffard was to fill his balloon not with hot air, but with hydrogen, a gas lighter than air.

On September 24, 1852, Giffard took off in his airship from the Paris Hippodrome. The propeller reached a speed of 120 revolutions per minute - the engine did not have enough power for more. The audience saw that the airship could fly in any direction at the will of the pilot.

Subsequently, there was a second airship (volume 3200 m3) with larger geometric dimensions (70 m long and 10 m across) and a more powerful engine. While working on the new engine, Henri Giffard invented a steam injector (Giffard injector), for which he received a patent (later this injector became widespread in industry). Then Giffard began to build large airships designed to lift a large number of people. In 1867, he produced a 5000 m3 airship for the World Exhibition in Paris, and in 1869, in London, he presented a 12,000 m3 balloon for lifting 30 people to a height of 600 meters. And in 1878, at the new Paris exhibition, he offered a 25,000 m3 balloon. The device lifted 40 passengers in a gondola to a height of 500 meters. During the 2.5 months of the exhibition, 40 thousand visitors took to the skies in it. This record for the balloon's carrying capacity remained unsurpassed until the advent of Ferdinand von Zeppelin's airships in 1914.

But Giffard dreamed of the future and harbored a dream of building a truly gigantic airship. So in the early 1880s, he began to develop a project for an airship with a volume of 220000 m3 and a length of 600 meters. However, it did not come true. Giffard died in April 1882. He bequeathed his entire fortune to various scientific societies, and a significant part to the poor of Paris.

However, Giffard's projects were not in vain. His experience was taken into account by other inventors: aeronautics as a passion for flying was slowly capturing people of all walks of life in Europe.

Dreams and developments of Count von Zeppelin

The German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin became one of the enthusiasts of ballooning. He became "infected" with it in the United States during the Civil War. It took him only one flight over the Missouri Valley to get over it. This event not only changed the life of the count himself, but also significantly influenced the history of aeronautics.

During his stay in the United States, von Zeppelin was constantly concerned with this topic: he prepared designs for aeronautical vehicles, convinced his military leadership of the prospects of using aeronautics in military affairs, dreamed and experimented with materials and engines. Experts are rather cold to his inventions, and his military colleagues even mock his fantasies. But the count himself does not give up his dreams.

Finally, his military service is over: he is already a lieutenant general. His pension and the income from his family's estates should provide him with a comfortable and peaceful life.

But this is not for him. He finally felt that he had the opportunity to recall his dreams of aeronautics and flying.

His plans stretched far beyond his native Fotherland, to Africa and even the uncharted expanses of the Arctic. And his acquaintance with the founder of the Universal Postal Union, von Stefan, convinced him that there was a huge demand for postal and passenger routes in the world, in particular, for the transportation of mail to the most remote corners of our planet. This would have commercially justified his aeronautical projects.

Meanwhile, at the beginning of the twentieth century, many people in the world became interested in ballooning. Among them was the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont, who considered himself the first "air athlete." His flight around the Eiffel Tower on October 19, 1901, in a blimp of his own design, brought him 100,000 francs in prize money and worldwide fame.

In Germany itself, another aeronautics fanatic, the Hungarian David Schwartz, worked to design all-metal airships. After his death, von Zeppelin acquired the patents of the deceased from his widow. Soon after, the famous German journalist Hugo Eckener joined von Zeppelin's team and helped the business flourish.

As is usually the case, the count was plagued by setbacks at first. His first two airships were constantly crashing. In addition, the designer simply lacked funds. But on the third device, when the 68-year-old general's estates were mortgaged and he faced the prospect of begging, a real miracle happened. The military department liked his model of the airship: the military first purchased one airship, and later ordered three more. The LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin airship conquered the whole world. In 1909, there were so many orders that the Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin Gmbx company had to be founded, which quickly became a trendsetter around the world, and a little later, the DELAG company, which was engaged in intercontinental passenger transportation.

By the outbreak of World War I, Zeppelins had already made 1588 flights, transported more than 34 thousand passengers and a lot of cargo, including mail.

And during the First World War, the Zeppelin concern built more than 100 airships. The journalist Eckener became a pilot instructor.

Unlike the first airplanes, airships were capable of lifting huge loads of bombs into the air and dropping them on the enemy with great accuracy. This was confirmed by the brutal destruction of London and Antwerp with numerous casualties as a result of airship bombing.

Count Zeppelin died in 1917. And 20 years after him, the golden age of airship construction came to an end with the death of the Hindenburg airship.

Meanwhile, in Kyiv...

Among those who stood at the origins of aeronautics, we should also mention our compatriot, Kyivan Fedir Anders.

In Kyiv, the center of aeronautics development was the Kyiv Aeronautics Society, founded in 1909, which included representatives of various segments of the population. The society held aeronautical exhibitions, demonstrating aircraft designed by its members, technical literature, organized charity evenings ("aeroball"), and organized flights and pilot training.

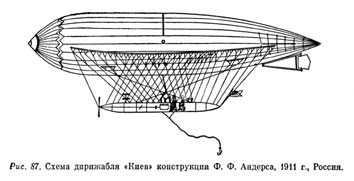

One of the most ardent enthusiasts of aeronautics in Kyiv was a technical employee of the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute, Fedir Anders, a man of extraordinary destiny and exceptional talent. He became the first in the Russian Empire to develop a soft-body airship. Without a university degree, Fyodor Anders managed to prepare technical documentation for the design of his own airships.

In January 1911, a charity aeroball was held at the Kyiv Public Library (now the Yaroslav the Wise National Library of Ukraine). In addition to the exposition of the technical achievements of the Aeronautical Society, Anders' design was also presented.

Partly with funds from charitable contributions and partly with his own savings, Fyodor Anders built an airship, the main element of which was a spindle-shaped cylinder made of special fabric filled with hydrogen. A nacelle was attached to it with rope slings, which contained controls, a power unit, a fuel supply, a pilot, and passengers or cargo. The designer named his vehicle after his hometown, Kyiv.

In the fall of 1911, he, his son, and a mechanic flew their airship over Kyiv for the first time. Subsequently, for almost a year, demonstration flights were performed, starting over the Merchants' Assembly Garden (now the National Philharmonic of Ukraine) and Dumska Square (now Independence Square). Anders proposed to organize commercial flights with passengers and advertising on board, a first in the empire. In total, his airship made about 160 flights...

Airships today and tomorrow

Lighter-than-air aircraft are still in use today. Moreover, in 1993, the legendary Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin Gmbx was revived and now it is called Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik. Its most advanced product is the Zeppelin-NT passenger airship, which is operated in several countries. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, prototypes of military airships for surveillance and reconnaissance were developed and tested. Hybrid airships for the transportation of bulky cargo are considered promising. There are many different designs of remotely piloted mini-dirigibles and autonomous robot airships for various purposes, etc. So the history of airships does not end there...