On June 15, 2021, a prominent Ukrainian scientist in theoretical mechanics and teacher, two-time winner of the State Prize of Ukraine and O.M. Dynnyk Award, Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Professor Mykola Oleksandrovych Kilchevskyi (1909 - 1979) would have turned 112 years old. Several generations of scientists and engineers from Ukraine and all the republics of the former Soviet Union grew up on his textbooks and manuals. They are up-to-date even to this day. For many years Mykola Kilchevskyi had worked at Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. He was not only brilliant in teaching but also very demanding. So, it was not easy to learn from him. His insistence contributed to perseverance in learning and, consequently, the acquisition of perfect knowledge. No wonder his students and disciples remember his name with gratitude today. One of his students was Professor Leonid Golyshev. The “KP” newspaper offers its readers very engaging recollections of Leonid Golyshev about Mykola Kilchevskyi and his studies at Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute in the 1950s.

In 1953, after graduating from school, I came from Chisinau to enter the Faculty of Engineering Physics of Kyiv Order Lenin Polytechnic Institute. The Admissions Committee explained to me that the specialties I was interested in became part of the Faculty of Radio Engineering. The faculty dean, Professor Volodymyr Ohiievskyi, suggested choosing “Electronic devices” because the specialty prepared engineers-physicists of the relevant profile.

How difficult the training turned out to be! The first thing was a large number of subjects of the physical and mathematical approach. Secondly, subjects on the theoretical foundations and methodology of engineering. Thirdly, professional subjects in the specialty were also a challenge! Besides, the History of the All-Union Communist Party, Fundamentals of Marxism–Leninism with the elaboration of primary sources, Political Economy, and others. There were almost no textbooks, so we carefully kept notes.

Among our teachers were legendary professors whom we deeply respected: disciples of Academician Mykhailo Kravchuk. They were: Alexander Smogorzhevsky (analytical geometry, methods of mathematical physics) and Valentyn Zmorovych (mathematical analysis), Academician Adrian Smirnov (atomic physics), Head of our profile department Academician Serhii Svechnikov (then still an Associate Professor), and others.

First of all, however, I want to tell you about Professor later Academician Mykola Oleksandrovych Kilchevskyi (hereinafter – M.O.). At that time, there was a certain contradiction of his image in the eyes of students and mine. However, he remained an unattainable ideal of a teacher for me. M.O. taught us Theoretical Mechanics and Analytical Mechanics from the 3rd semester. In addition, he had the course of General Physics as part of the Mechanics academic discipline.

We first saw him in a large auditorium on the 1st floor of the main campus building. There came two 2nd-year groups, FD-6 (ФД-6) and TE-6 (ТЕ-6). A mature (under 50 years old), fit and stern man with gray hair in wavy hair came into the classroom. He was wearing a pilot coat because he headed the Department of Theoretical Mechanics at the Kyiv Institute of Civil Air Fleet then and had the right to wear a uniform. Later, he began wearing a dark blue gabardine double-breasted suit. One could not miss his gold-rimmed spectacles and the impenetrable and, at times, unkind eyes.

The senior students felt sorry for us. To get at least a satisfactory mark from him on the exam was already considered a success. At the same time, a good mark was great success and luck. No one even dreamed of an excellent from him. Only the group presidents who kept the group register and, probably, were exclusively conscientious, according to the professor. Only students-overachievers had some privilege.

M.O. announced to us his disciplinary requirements strict and categorical:

- do not enter the classroom after him;

- group presidents are obliged to mark all absent students in the class with “n” (i.e. absent) in the group register. A student had to explain the reasons for absence in the dean's office and get admission to further classes;

- there should be complete silence in the classroom, as any conversations between students, even whispers, interfere with the learning process;

- when a student has a question during the lecture, he should raise his hand. As soon as the Professor finishes his opinion or idea, he will answer the question;

- when a student did not understand some things in the lecture or had other questions, he could come for a consultation at the Department of Theoretical Mechanics (on Tuesdays and Fridays). A student had to make an appointment first with the assistant. We had L.V. Kirsa.

Other professors did not put us in such conditions. We studied their disciplines because we deeply respected them. We were wary of them but just a little. As for Professor Kilchevskyi, we respected him, but we were also afraid of him at the same time.

Before lecturing new material, M.O. used to interview 2-3 students on the previous lecture. At the same time, the Professor looked up another victim in the group register and, flashing his glasses predatorily, said loudly: “Student Ivanov!” Ivanov stood up to attention and squeezed out in a trembling voice: “Me".

The Professor looked at the probable victim with a predatory look and quickly asked questions. If a student paused, M.O. would state: “There is no answer. Obviously, you did not find time to prepare. If you look in the group register, you will see that you were present at the previous lecture. Take your seat: your score is a two. See you at the consultation on Friday but make an appointment with the assistant first.”

Then there were 1-2 more students who convulsively compressed their notes.

Many people went to the consultation. The Department of Theoretical Mechanics had two adjacent rooms: the first was for teaching staff, the second was the Department Head office. There was a kind of a bedside table at his office door. Just above the bedside table hung a sign which said, “Head of the Department, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Professor Mykola Oleksandrovych Kilchevskyi asks the department staff not to use the telephone in his presence, as telephone conversations interrupt his work.”

At the Department of Theoretical Mechanics M.O. was both king and god. As it turned out, all the department staff were also his students in the past, except for Associate Professor (later Professor) Tetiana Putiata. She graduated from Academician Dmitry Grave.

Mykola Kilchevskyi gave lectures on theoretical mechanics not only at Kyiv Order Lenin Polytechnic Institute and the Kyiv Aviation Institute but also at Kyiv State University. He later published excellent textbooks in Ukrainian as well. It was Academician Mykhailo Kravchuk, an outstanding student of Academician Dmitry Grave, who worked fruitfully and, thus, created Mykola Kilchevskyi the basis on the relevant physical and mathematical terminology. By the way, I could not find out whose postgraduate student M.O. was at Kyiv State University. The only thing I have found out about his doctoral program is that his thesis advisor at the Institute of Mathematics of the USSR Academy of Sciences was also a student of Academician Dmitry Grave, Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Professor Illia Shtaierman.

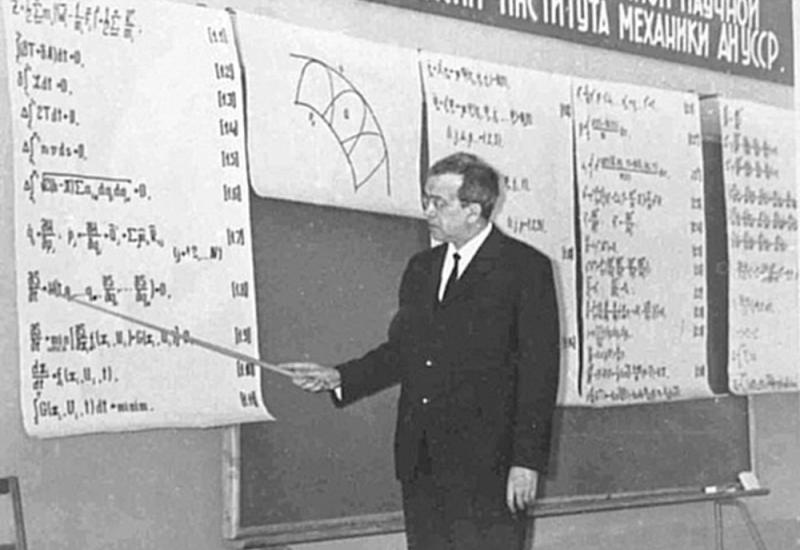

M.O. had a peculiar nature of teaching the discipline. His lectures were a rational combination of deep knowledge of the subject, a strict and concise performance. He supported his style with stingy gestures and the squeak of chalk. By the way, it was the duty of group presidents to arrange chalk and a damp cloth. Everything was very scholastic and strict. He used every inch of the blackboard and clearly articulated the material. All the essential formulas and calculations remained on the board until the end of the lecture. When I started teaching, I never managed to cope with the board, no matter how hard I tried. During the lecture, he made short pauses to record the calculations in the materials. At the same time, he watched the audience and cast formidable glances at those students who had not worked diligently enough on the synopsis. At that time, there were no recommended textbooks on the subject.

He was very nervous when anyone invaded the silence in the lecture hall. Few students were aware that such silence in the lecture hall was crucial for him. He did not teach the memorized material, peeping into his notes. On the contrary, he was in the process of creative reflection of the lecture. Of course, he did not want to indulge in our weaknesses.

No jokes were allowed in lectures. And whether this extremely closed person had a sense of humor remained unknown to me. Here is one typical case. Once, drawing a complex conclusion on the board, M.O. stopped, returned to the audience, and, looking up into the ceiling, solemnly and theatrically said: “... Now I will apply the method ... (pause), which ... (the audience froze in anticipation of the sensation). .. a hundred years ago ... used the great marquis de Laplace!” Someone laughed in the audience. Oh, if only you had seen what happened then! The enraged Professor burst with anger: “What-oh-oh, are you laughing at science?!” He threw chalk on the floor and demonstratively left the lecture hall. During the break, Deputy Dean Yu.V. Mykhatskyi, if I am right, came into the lecture hall, scolded us, and advised us to apologize. But none of us had an evil intention and close! As I realized much later, it was just a nervous breakdown of an overworked creative person.

It occurred to me, then, that, probably, M.O. considered Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace very significant. He once said that Academician Mikhail Ostrogradsky, the citizen of Poltava, was a student of Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace. In his memoirs, Mikhail Ostrogradsky said that Laplace was a fierce professor. Once, he witnessed how the assistants carried the next examinee on a stretcher out from the class, where Laplace took an exam. The exam usually allegedly began with a student writing from memory all the basic formulas of his, Laplace, “Celestial Mechanics”. And only after that, the great scientist began further execution.

Probably, in M.O.’s opinion, traits, like being demanding to students, stinginess, and often bias in assessing their knowledge made him close the legendary Laplace. And, probably, we can forgive such demands because even then, he had every reason to consider himself the greatest mathematician-mechanic in the country. Students, of course, could not understand this, especially since his scientific publications were not available to us. Now, the information posted on the S. P. Timoshenko Institute of Mechanics website (in which M.O. had worked for the last 18 years of life), let us know that a two-volume textbook by M. Kilchevsky was recognized as the best textbook of theoretical mechanics in Russian. It was published in 1977 by the Moscow publishing house “Nauka” (“Science”).

As a teacher, he wanted to ensure that absolutely all students master the course. At least they had to memorize the basic terms, definitions, theorems, and laws. I remember an incident when a student dissatisfied with the grade on the exam got up the courage to retake it. The dean's office gave such permission. A student enrolled at the Department and had to pass the exam again in the professor's office. In that case, M.O. took the test: he crossed out the exam grade and interviewed a student very carefully throughout the course. Most often, the mark remained the same or even lower. While a student got an experience, he would never forget, M.O. did not treat him better. That is what I think.

Many people remembered M.O. as a very arrogant and spiteful man. He asked questions, often quite simple, in such an angry tone that many, even the most successful, were lost and could not answer. At the same time, for example, Professor A.A. Smyrnov managed to work with students in such a quiet way that even weak students answered quite complicated questions.

Frankly speaking, only over time did I realize how great our teacher was in science. And his demand to observe absolute silence during lectures, when he was deeply immersed in the creative process, was absolutely fair. And we were absolutely unfair when we mocked his demands and said annoying remarks behind his back. He always worked hard, though had a delicate and vulnerable nervous system. M.O. was doing his best to perform honestly and often worked with not very mathematically gifted students.

М.О. used to give tests in the last 20 minutes of the lecture. In the following lecture, the Professor announced the results. And often all students got a 2 and heard a relevant comment. However, group presidents and appointed A-students received good marks. One day, after all, students got a 2, when I was sitting quietly, to my surprise, I suddenly heard my last name. I stood up. The Professor looked at me through his golden spectacles, returned to the audience, and said with triumph in his voice and gaze, “What do you think which mark I could put a student who made two grammatical errors in the word “ellipsoid”? He wrote “e-liap-so-id!” He smiled bitterly and, lowering his voice, said almost in a whisper, “You have a 3.” The students reacted with a friendly laugh. I wanted to prove something but stopped in time, and thank God! Unfortunately, M.O. remembered me.

There was a bookstore on Volodymyrska Street, next to the Opera House. Sometimes I used to buy books there. Once I bought a book by Gaspar Coriolis “A Theory of Billiards” and immediately open it to take a look inside. Suddenly, someone's hand reached out to my book. It was Professor Kilchevsky's white hand. He looked at the cover, grinned vaguely, and said something like well-well. He did not say a word to me. However, M.O. had a good memory. Probably, he remembered me as a hoodlum. During the exam, he remembered something, and with noticeable pleasure and completely unexpectedly for me, he put me a 3…

I also was connected with M.O. through public relations. Three students of our group (TE-6) out of 25 were about 10 years older: two men who had been in the war and one woman who worked in production. Physical and mathematical disciplines were very complicated, especially for them. There was a tradition according to which every Komsomol member had a constant social burden. I had to help the elderly Ivan Pakhomovych Pavlov, a polite, decent man, a turner of the highest rank. He had a bad habit of using indecent language - automatically and absolutely harmlessly. He struggled with this habit in a peculiar and long way. Saying a phrase, he suddenly went into a whisper, uttered almost silently the mother's insert, and continued the interrupted idea in a voice as if nothing had happened. So the girls from the group, and most likely the teachers, did not notice anything.

About once a week, I came to the dormitory, gave my lectures to Ivan Pakhomovych, and helped him with an extracurricular assignment. As soon as the session came closer, he became sadder and said, “Lionia, screw the whole thing. I give up and will go to Karelia to log and pick berries.” Each time I persuaded him to prepare for the exams, pass and retake them, lose the scholarship for a while (he compensated for this by unloading coal on the railway at night), and then to start all over again.

After three unsuccessful attempts by Pavlov, I had to ask Professor Kilchevsky to retake the exam and be indulgent to Pavlov, who had difficulties in studying. M.O. replied that if Pavlov did not cope with training, he could choose another profession. But somehow, Ivan Pakhomovych settled his affairs and, in the end, successfully graduated from the institute. He later worked successfully, was the head of the laboratory at a large defense instrument-making enterprise, and a typical “master of the golden hands”.

However, M.O. also did not forget me at all. At the faculty party meeting, as I was told, the then non-party M.O. complained that some employees of the dean's office and students put pressure on him. He said that a student Golyshev repeatedly had come to ask him to give a positive assessment to his ward, student Pavlov. “What mark did Golyshev get in my exam?” asked M.O. – “A three!’ His words made noise at the meeting.

In conclusion, I want to say that our group can boast with worthy specialists. We had two doctors of physical and mathematical sciences: Iryna Borysivna Yermolovych and Heorhii Yevhenovych Chaika. And two doctors of technical sciences - Volodymyr Ivanovych Osynskyi and me, the author of these lines…